Why I’m Doing This Project

When studying fluid mechanics, it’s easy to get lost in the equations and forget the real flow behind them. This semester, I wanted to reconnect with the hands-on side by building something that lets me feel the airflow instead of only simulating it.

The idea emerged from a question that often strikes me when watching planes take off: how exactly does that tiny Pitot tube on the fuselage measure airspeed so precisely?

So I decided to build one myself: a connected Pitot probe, combining an Arduino for data acquisition and Wolfram Mathematica for real-time analysis and visualization.

Along the way, I hope to refresh the theoretical foundations, design a small and functional airspeed sensor, and share a clear, visual narrative for anyone curious about experimental fluid mechanics. Ultimately, this project is my way to bridge two worlds I love: analytical modeling and hands-on experimentation.

StreamPlot[

{1, -0.3*y/(x^2 + y^2)},

{x, -2, 2}, {y, -1, 1},

StreamPoints -> Fine,

StreamStyle -> Blue,

Epilog -> {Red, PointSize[Large], Point[{0, 0}]},

PlotLabel -> "Flow field near a stagnation point"

]

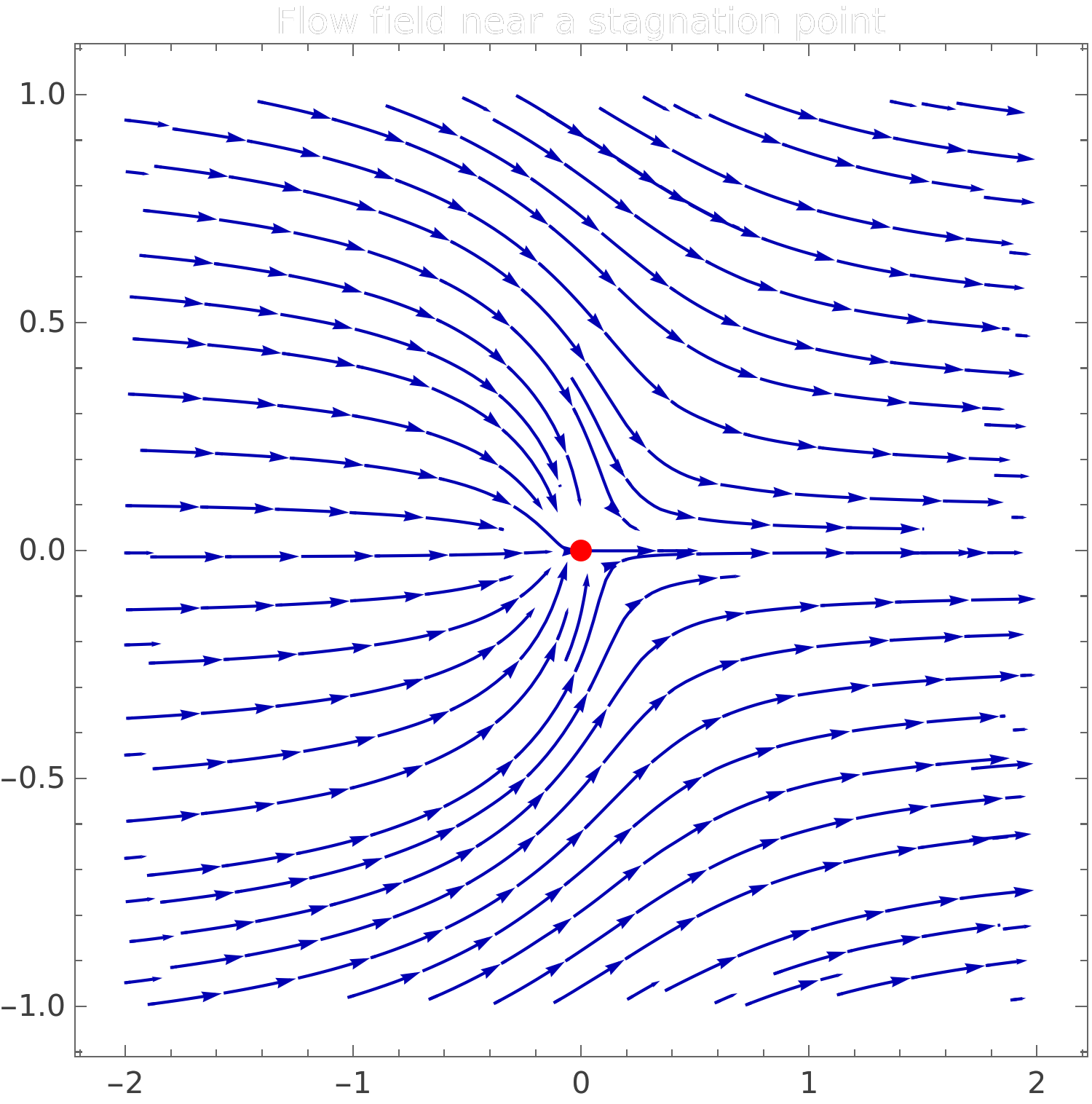

Figure 1 • Streamlines around a stagnation point, highlighting where the Pitot tube senses total pressure

How a Pitot Tube Works: A Short Theory Refresher

The Pitot tube is a deceptively simple device. It measures the difference between the total pressure (where the flow stagnates) and the static pressure (of the surrounding air). This small difference corresponds directly to the kinetic energy of the moving fluid.

We start from the Bernoulli equation for an incompressible, inviscid, steady flow along a streamline:

$$p + \frac{1}{2} ρ v^2 + \rho g z = constant$$

Between a point in the free stream (velocity v, pressure ps) and the stagnation point at the tip of the Pitot tube (velocity 0, pressure pt), assuming they are at the same height, we obtain:

$$p_t = p_s + \frac{1}{2}\rho v^2$$

Rearranging gives:

$$v = \sqrt{\frac{2(p_t − p_s)}{\rho}}$$

The Pitot tube effectively measures the dynamic pressure Δp = pt − ps. We can then compute the velocity using this equation, adjusting for air density as needed.

Assumptions and Practical Limits

- The flow is treated as incompressible, which is a good approximation at low to moderate airspeeds.

- The flow near the probe is assumed steady and uniform over the time scale of the measurement.

- Viscous losses and tubing effects are neglected in the basic formula, although they can introduce small biases.

- The air density ρ can be approximated as constant, or computed from ambient temperature and pressure using the ideal gas law.

These assumptions are perfectly acceptable for a small experimental setup with modest flow velocities. They allow us to focus on understanding the measurement chain without getting lost in corrections that matter primarily for high-speed aerodynamics.

Manipulate[

Plot[

0.5*rho*v^2,

{v, 0, vmax},

Filling -> Axis

],

{{rho, 1.2, "ρ (kg/m³)"}, 1.0, 1.3, 0.01},

{{vmax, 50, "Max velocity"}, 10, 100, 1}

]

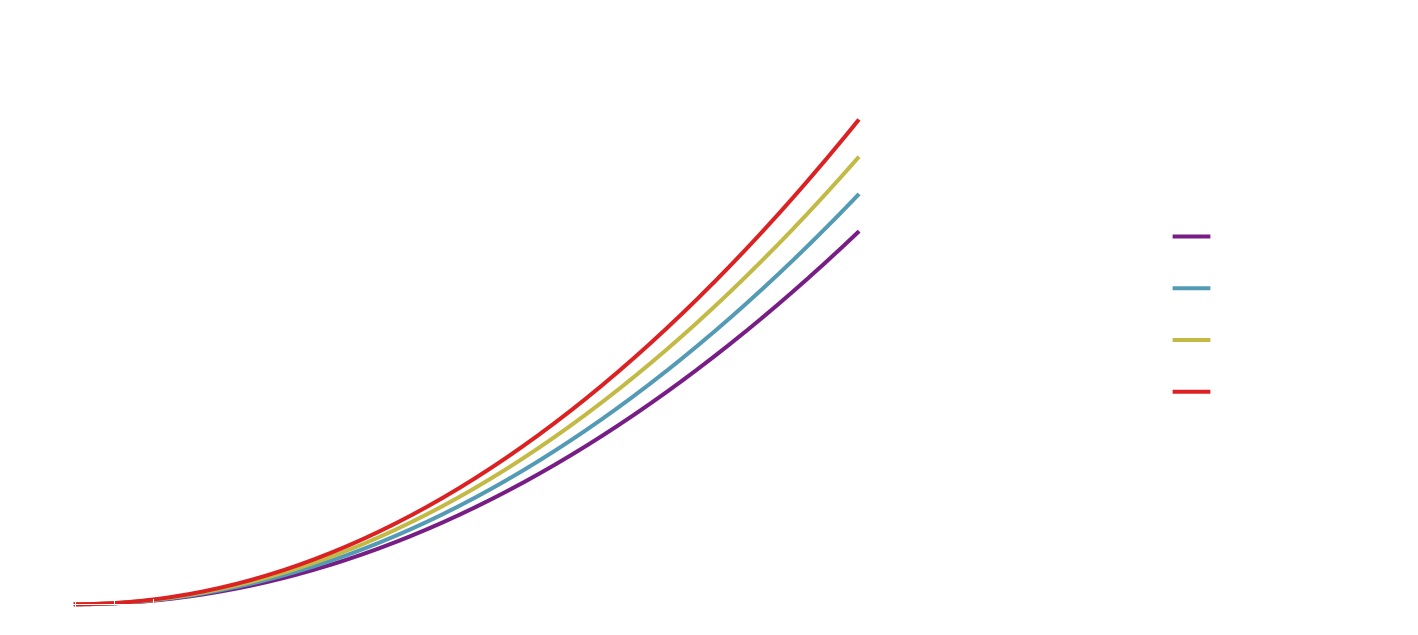

Figure 2 • Dynamic pressure Δp as a function of velocity for different densities, illustrating the quadratic dependence predicted by Bernoulli’s equation.

Time for implementation!

Building the actual device began with the simplest possible material: PVC. Instead of using metal tubing, I wanted a construction method that was inexpensive, easy to reproduce, and safe to drill. I used a short piece of small-diameter PVC pipe, the kind sold for aquarium air lines. To form the stagnation port, I cut the front of the tube cleanly and smoothed it with fine sandpaper so that the airflow would meet a sharp, well-defined edge.

To create the static ports, I drilled two tiny lateral holes near the front using a 1 mm micro-bit and a hand drill. Drilling the holes symmetrically on opposite sides ensures that lateral pressure components cancel, giving a clean estimate of the true static pressure. With this very lightweight PVC probe, I could already capture the pressure distribution Bernoulli’s law requires.

Once the sensing ports were ready, I attached two flexible PVC hoses to route the pressure channels to the differential pressure sensor. PVC is cheap, stiff enough not to collapse at low pressure, and seals well: warming the tube ends a few seconds over gentle heat softens the material enough to press-fit it onto the sensor barbs with an airtight seal. This created a simple but reliable pressure line from the Pitot ports to the MPXV7002DP. To document the hardware, I drafted a small schematic showing the PVC Pitot, the two pressure lines, and their connection to the sensor and Arduino.

Figure 3 • Homemade PVC Pitot tube connected to two PVC hoses feeding the differential pressure sensor, and Fritzing schematic showing the Pitot tube, pressure sensor, and Arduino connections.

With the physical system assembled, I moved on to data acquisition. The MPXV7002DP outputs a voltage proportional to the pressure difference between its two ports. Its output is analog, so the Arduino’s ADC simply reads the voltage on one of its analog inputs. The electrical setup is minimal: 5 V and GND for power, and the sensor’s output connected to A0.

The Arduino sketch continuously reads the analog value, converts it to volts, subtracts the nominal offset (the sensor’s zero-pressure output), computes Δp in kilopascals, and streams each measurement over USB serial. I deliberately kept the code short and simple, letting Mathematica handle all downstream processing and visualization.

const int pin = A0;

const float Vcc = 5.0;

const float offset = 0.5; // Sensor output at 0 kPa

const float sensitivity = 0.5; // Volts per kPa for MPXV7002DP

void setup() {

Serial.begin(115200);

}

void loop() {

int raw = analogRead(pin);

float voltage = raw * (Vcc / 1023.0);

float dp = (voltage - offset) / sensitivity; // Δp in kPa

Serial.println(dp, 4);

delay(10); // ~100 Hz

}

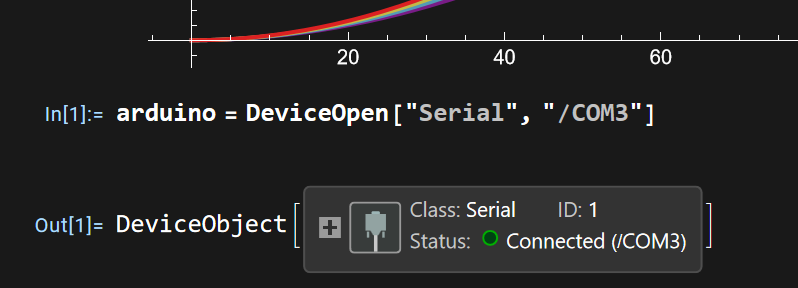

Connecting Arduino to Wolfram Mathematica

Mathematica communicates with the Arduino through its built-in serial device framework. After plugging the Arduino in, I listed the available serial ports, opened the correct one, and began reading the pressure stream in real time. The idea is simple: each line sent by Serial.println on the Arduino becomes a value that Mathematica can parse and process.

arduino = DeviceOpen["Serial", "/COM3"]; Dynamic[ currentDP = ToExpression @ DeviceRead[arduino]; currentDP ]

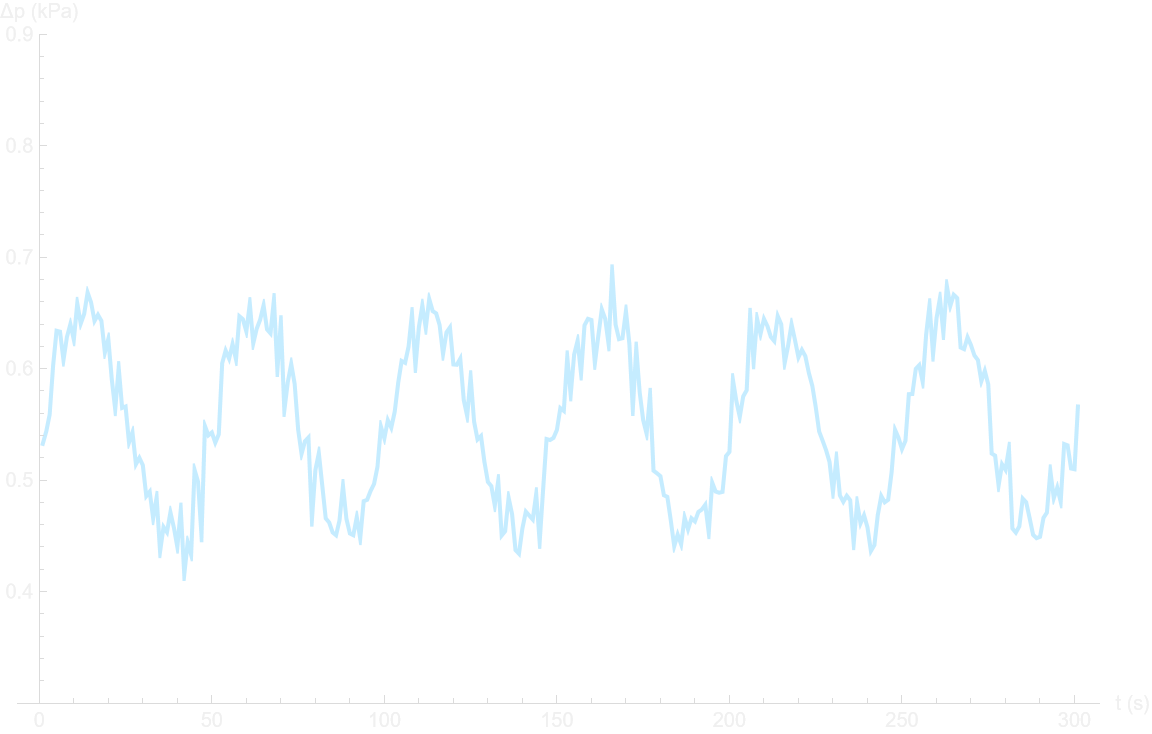

The first measurements were understandably noisy, reflecting both the sensitivity of the sensor and the turbulent nature of the airflow produced by a desk fan. To stabilize the readings, I added a moving average and a simple low-pass filter directly in Mathematica, which immediately made the signal more interpretable.

Figure 5 • Connecting the Arduino to Wolfram Mathematica and getting the first (noisy) signals back

Converting Pressure to Velocity

With a stable stream of Δp values, turning pressure into velocity became a direct application of Bernoulli’s relation. Assuming an air density of ρ = 1.20 kg/m³, the velocity is given by

$$v = \sqrt{\frac{2\Delta p}{\rho}}$$

Since the Arduino sends Δp in kilopascals, Mathematica converts it to pascals and applies the formula above. I wrapped this in a small function and used Dynamic to obtain a live readout of airspeed.

rho = 1.20; (* kg/m^3 *) velocity[dp_] := Sqrt[2*dp*1000 / rho]; (* dp in kPa -> Pa *) Dynamic[ velocity[currentDP] ]

Calibration and Validation

To check that the system behaved realistically, I carried out a simple calibration by placing the PVC Pitot tube at different distances in front of a fan set to fixed speeds and recording the corresponding Δp and velocity estimates. Although this is not a wind tunnel, the resulting data followed the expected quadratic relationship between dynamic pressure and velocity.

(* measuredData: list of {v_measured, dp_measured} points *)

ListPlot[

{measuredData, theoreticalCurve},

PlotRange -> All,

PlotLegends -> {"Measured", "Theory"},

AxesLabel -> {"Velocity (m/s)", "Δp (Pa)"},

ImageSize -> Large

]

Even with this very simple experimental setup, the agreement was good enough to validate the concept: a low-cost PVC Pitot tube, a single pressure sensor, and a few lines of code were sufficient to turn Bernoulli’s equation into a live, interactive measurement of airspeed.